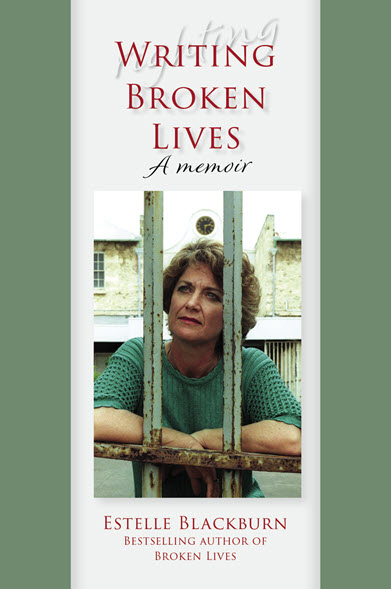

Estelle has recorded why and how she went about her extraordinary work of investigative journalism, Broken Lives, in her memoir The End of Innocence, launched at the June 2007 Sydney Writers Festival.

Was unavailable for a few years and because of high demand, Estelle has updated it and republished it as Writing Broken Lives. Coming soon – See www.echobooks.com.au/biography/writing-broken-lives/

Writing Broken Lives – updated The end of Innocence – published soon.

At that moment, Button and Beamish remembered how close they had come to such a fate. Button had been taken off Death Row five months earlier by the jury that returned the verdict of manslaughter over his capital wilful murder charge; Beamish’s 1961 wilful murder death sentence had been commuted by the State government. The two youths realised at that moment there would be no reprieve on their sentences. The noose that had just killed prisoner 21649 had also killed any hope Button and Beamish had of proving they were innocent. Button faced ten years with hard labour, and Beamish was incarcerated for life.

At that moment, Button and Beamish remembered how close they had come to such a fate. Button had been taken off Death Row five months earlier by the jury that returned the verdict of manslaughter over his capital wilful murder charge; Beamish’s 1961 wilful murder death sentence had been commuted by the State government. The two youths realised at that moment there would be no reprieve on their sentences. The noose that had just killed prisoner 21649 had also killed any hope Button and Beamish had of proving they were innocent. Button faced ten years with hard labour, and Beamish was incarcerated for life.

Eric Edgar Cooke was executed at 8 a.m. on Monday 26 October 1964, in the last act of capital punishment in Western Australia. He had confessed to twenty-two violent crimes — eight murders and fourteen attempted murders and assaults — during a five-year period between September 1958 and September 1963.

The detectives refused to accept two of these twenty-two confessions. They declared Cooke was lying when he voluntarily confessed in intricate detail to the 1963 hit-run murder of John Button’s seventeen-year-old girlfriend Rosemary Anderson, and in similarly accurate detail to the 1959 axe murder of Jillian Brewer, a 22-year-old heiress from Melbourne.

When Cooke was captured, John Button and Darryl Beamish had already been convicted of these murders. Each of the nineteen-year olds had confessed during long, terrifying police interviews held in the absence of parents or lawyers. But both claimed their innocence from the moment the detectives allowed their parents access to them, and pleaded not guilty, insisting that their confessions had been concocted by the detectives and signed only because of verbal and physical harassment.

After Cooke’s revelations, Button and Beamish appealed, requesting new trials at which juries could consider Cooke’s confessionsas well as their own. But these appeals were dismissed. In 1964, the judges of the Court of Criminal Appeal of Western Australia and then the High Court of Australia also refused to allow juries to decide the veracity of the confessions, taking it upon themselves to decide that Cooke was lying. Beamish lost a further appeal to the Privy Council in London in 1965.

With every legal avenue exhausted, Button and Beamish served their prison terms until paroled. They carried on with their lives in Perth, both marrying. But they wanted their names cleared. Darryl Beamish, a deaf mute, gave up after the loss of five appeals. John Button persisted in his efforts to have his case re-opened, requesting files from authorities and pleading with various Premiers, but in vain.

With every legal avenue exhausted, Button and Beamish served their prison terms until paroled. They carried on with their lives in Perth, both marrying. But they wanted their names cleared. Darryl Beamish, a deaf mute, gave up after the loss of five appeals. John Button persisted in his efforts to have his case re-opened, requesting files from authorities and pleading with various Premiers, but in vain.

Three decades later, their hope was renewed when a fateful meeting stirred my curiosity and set me on a course of investigation that turned into a crusade. It took me six and a half years to research and write the book, Broken Lives. It was first published in November 1998, with invaluable editing and guidance from Zoltan Kovacs and generous financial and other support from Bret Christian OAM, and contained enough fresh evidence to move the government of Western Australia to grant new appeals to both John Button and Darryl Beamish — almost four decades after their former appeals.

Barrister Tom Percy QC and solicitor Jonathan Davies volunteered to act pro bono for both men. John Button’s case was heard before the Court of Criminal Appeal in May 2001, before Chief Justice David Malcolm, Justice Henry Wallwork and Justice Neville Owen.

Bret and I assisted the legal team, which also included Bill Chestnutt, Gaetan Von Der Becken and Frank Voon, with help from John and Helen Button, their daughter, Naomi, and Gordon Hattock. As well as the fresh evidence revealed in Broken Lives, another important witness appeared: the WA Police Force’s fatal accident vehicle examiner, Trevor Condren, who had examined Button’s car in the police yard in 1963. Another key witness was international crash reconstructionist Rusty Haight, whose trips to Perth, scientific testing and evidence were a crucial contribution by Bret to John Button’s successful appeal.

On 25 February 2002, John Button was exonerated. His 1963 conviction of the manslaughter of Rosemary Anderson was quashed by the Court of Criminal Appeal in what Chief Justice David Malcolm described as a miscarriage of justice. From the age of nineteen to fifty-eight, John Button had lived his life as a convicted killer. Now, thirty-nine years later, his name was cleared.

The case made legal history on two counts: it was the longest-standing conviction in Australia to be overturned, and it was the first time propensity evidence was accepted by an Australian court. In 2003, the government of Western Australia acknowledged the injustice wrought on John Button with an ex-gratia compensation payment of $460,000.

Darryl Beamish’s new appeal, his sixth, was heard in the Court of Criminal Appeal in October 2004, before Justices Chris Steytler, Christine Wheeler and Carmel McClure. Tom Percy QC and now-barrister Jonathan Davies acted pro bono, with the legal assistance of Frank Voon, Michael Dawson and Katie White, a major effort by Bret Christian and help from myself.

On 1 April 2005, Darryl Beamish was exonerated. His 1961 conviction of the wilful murder of Jillian Brewer was quashed by the Court of Criminal Appeal, which said there had been a substantial miscarriage of justice. It was forty-four years after his wrongful conviction and death sentence. The journey to justice has been long and harrowing for both these innocent men and their families. It’s very likely they would never have reached this goal had fate not crossed our paths.